Digestion

| << Previous | Summary | Next Topic >> |

Introduction:

The digestion process is briefly outlined below for the purpose of learning how to develop meal plans that satisfy your hunger, are easy to digest, efficiently absorbed and promote intestinal health. Questions that will be looked at are; how many meals per day are optimum, how much time should be allowed between meals, is snacking healthy, is drinking with meals okay, should food combining guidelines be followed, what's the best volume and density (richness) and so forth. At the end, a list of tips for good digestion is included.

Digestion Process:

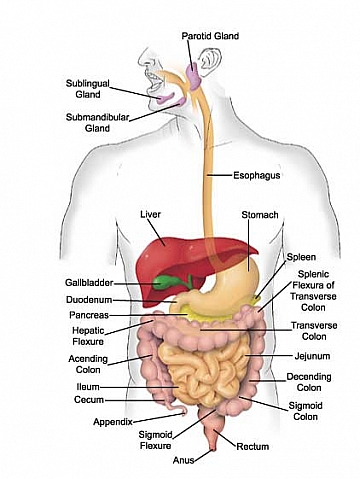

The gastrointestinal tract handles the processes of digestion, absorption and elimination. It is about 30 feet in length and includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. The flow of food from one organ to the next is controlled by sphincters which assist in keeping the flow going in one direction and containing the various chemical reactions unique to each organ.

Digestion begins in the mouth. Chewing food breaks it up into finer parts, mixes it with saliva and makes it easier to swallow. This also increases its surface area so that it can be more efficiently acted upon by digestive juices. Saliva contains mucin, a slippery liquid and amylase, an enzyme for breaking down starch. Little digestion actually occurs in the mouth since the amylase is only active until the food enters the stomach where it is then destroyed by stomach acids.

Digestion begins in the mouth. Chewing food breaks it up into finer parts, mixes it with saliva and makes it easier to swallow. This also increases its surface area so that it can be more efficiently acted upon by digestive juices. Saliva contains mucin, a slippery liquid and amylase, an enzyme for breaking down starch. Little digestion actually occurs in the mouth since the amylase is only active until the food enters the stomach where it is then destroyed by stomach acids.

Swallowed food passes through the pharynx into the esophagus. The esophagus is a thick-walled, straight, muscular tube which leads to the stomach. Food is propelled downward toward the stomach by gravity and peristaltic waves of muscular contractions and relaxations. At the entrance to the stomach is the cardiac sphincter (also called the lower esophageal sphincter or gastroesophageal sphincter) which normally remains tightly closed to prevent gastric juices from backing up into the esophagus. When food reaches the end of the esophagus, the cardiac sphincter relaxes to allow food to pass into the stomach.

Upon entering the stomach, food causes cells in the stomach lining to produce the hormone gastrin. Gastrin stimulates gastric glands to secrete gastric juices. Gastric juices include;

- Hydrochloric acid - slightly more acidic than lemon juice, HCL activates pepsin, starts to denature proteins and kills bacteria and germs.

- Intrinsic factor - a protein which assists in the absorption of vitamin B12.

- Pepsin - an enzyme that begins the breakdown of protein.

- Gastric lipase - an enzyme that begins the breakdown of lipids.

Most digestion and absorption occurs in the small intestine. The small intestine is about 20 feet long and an inch in diameter. It consists of three segments; the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The first 10 inches of the small intestine is called the duodenum. It completes most of the digestion. The jejunum and ileum handle absorption. The pancreas and gall bladder have ducts which empty into the duodenum. When chyme enters the duodenum, it generates the hormones; secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK). Secretin stimulates the pancreas to release bicarbonate which neutralizes the acidity of the chyme. Cholecystokinin stimulates the gall bladder to release its bile, the pancreas to release its digestive enzymes and the stomach to slow its gastric emptying. Bile is produced in the liver and stored in the gall bladder. When released into the small intestine, it serves to emulsify lipids, breaking them into small droplets that can be acted upon by enzymes. Several pancreatic enzymes become active upon entering the duodenum. They include amylase that breaks down starch into maltose (a disaccharide), proteases that break down proteins and lipase that digests lipids. The small intestine is lined with a heavily folded mucosal membrane that greatly increases its surface area. The mucosal membrane is lined with small fingerlike projections called villi which absorb the nutrients. The villi also produce some enzymes; maltase, sucrase and lactase, that break down their corresponding disaccharides (maltose, sucrose, lactose) into the final monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, fructose) which can be absorbed. Water-soluble nutrients (sugars, most vitamins, amino acids) are absorbed into the blood and passed to the liver via the portal vein. Fats and fat-soluble nutrients are absorbed into the lymph and circulated via the lymphatic system. After the digestion and absorption of nutrients is completed, the contents of the small intestine pass to the large intestine.

The main function of the large intestine is to absorb water, electrolytes (sodium, potassium) and short-chain fatty acids from the digested food mass received from the small intestine. It also stores the fecal matter until it is ready to be eliminated. The large intestine is about 5 feet long, has a smooth inner wall and surrounds the small intestine on three sides. It consists of seven sections; the cecum (a small sac where the small intestine attaches), ascending colon (right-side), transverse colon ( across the top), descending colon (left-side), sigmoid colon (S shaped), rectum and anal canal. There is a host of friendly bacteria living in the large intestine that feed on the undigested food matter. These bacteria help to break down short-chain fatty acids and to synthesize biotin, vitamin B12 and K. They also produce gases (methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen). As with the small intestine, the food mass is propelled along by peristaltic muscular contractions. As a side note, the B12 produced in the large intestine is excreted, not absorbed, since the absorption site for B12 is upstream in the ileum (small intestine).

For more information, see video Digestion Process 2:34 minutes.

Digestion Timeline:

There is considerable variation in the transit time of a meal through the GI tract depending on individuals and the content of the meal. Also, the meal does not move through the system in one mass. For example, food leaves the stomach in spurts over time. Food may first enter the small intestine within one hour after eating but it may take up to 4 hours for the stomach to completely empty. The estimates below are rough generalizations for a normal healthy individual eating a balanced diet.

Time in the stomach - 2 hours on average (up to 4 or even 5 hours in some cases)

Time in the small intestine - 4 to 6 hours

Time in the large intestine - 12 to 24 hours (up to 36 hours in some cases)

Total time for the passage of one meal - 18 to 32 (up to 46 or even 72 hours in some cases)

The type of food eaten, amount of fluids, overall health and age can make a big difference in transit times. The gut will be slower on a diet of refined carbs (low fiber) and dense foods (meat, pizza, cheese etc.) and limited liquids. A steak dinner can take two to three days to pass! However, if you stay well hydrated so that the urine is mostly clear and eat good portions of fruits and vegetables (high fiber), a meal will usually pass in 24 hours or less. Holding the byproducts of digestion in the large intestine for extended periods is unhealthy and in the long term, can lead various intestinal disorders.

To do a test, try eating a cup of beets at a meal. The stool will be red when it passes.

Meal Frequency:

How many meals a day is best? Assuming on average, a healthy adult consumes around 2000 calories per day, three meals per day seems to be the most practical. This means an average meal should be in the neighborhood of between 500-800 calories which is reasonable for a meal which is not heavily laden with fat or sugar. This also allows 4 to 7 hours between meals, giving time to be active and working without being encumbered by a full stomach all the time. Two meals a day is also a possibility. This would imply getting about 1000 calories from each meal. This option usually means skipping breakfast (lunch is the first meal of the day) or having a later brunch which replaces the traditional breakfast and lunch. However, the old saying that "breakfast is the most important meal of the day" still holds true according to most nutritionists. It is especially important for children in order to do well in school. Having breakfast moderates blood sugar levels, reduces fatigue and improves cognition. Skipping breakfast for weight loss reasons is not effective and in fact can have the opposite result! For those pressed for time, even the simplest breakfast (milk and cereal, nut butter and toast, fruit and yogurt) can make a difference. See Why Breakfast is the Most Important Meal of the Day.

A couple of studies have looked at the effects of eating one meal a day. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism. In summary, participants experienced increases in hunger, blood pressure and LDL levels (risk factors for cardiovascular disease). This is not a healthier alternative to the three meals a day regime.

Eating more than three meals a day can run the risk of increasing calories; something most Americans do not need. It can be inconvenient, requiring more time in meal planning and preparation. It will keep the digestive system working all the time, never giving it down time to replenish and making it difficult to do strenuous activity. During digestion, the blood supply is going into the digestive organs. Generally speaking, you need to wait two hours after a meal before engaging in strenuous exercise or activity. More than three meals a day can put a damper on being physically active. In a healthy individual, there are ample energy reserves between meals and there is no need to replenish every 2 or 3 hours. Previously, there were many advocates of six smaller meals per day. These recommendations generally came from two camps, those trying to lose weight who were told frequent eating would "speed up your metabolism" and body builders who wanted maximize protein intake and prevent muscle mass loss. Both these ideas have fairly been discredited and there has been a return to the old thinking that three square meals a day makes more sense. For more details see 3-Hour Diet or 3 Meals a Day? and also How many meals a day do you need to build muscle?. There may be medical reasons to eat more than three meals a day in order to moderate sugar levels or absorption. Diabetics or people with digestive disorders should follow the instructions of their health care provider.

Meal Composition:

Meals should be of sufficient volume to satisfy your hunger. The stomach has volume sensors and when it becomes extended, you feel full. The typical volume of a meal that is filling is between 2-4 cups. It is important not to overeat, that is, to the point of discomfort. Chronic overeating or eating all the time leads to many diseases and a shortened life span. Animal studies have consistently shown, that those on lean diets live longer and have fewer diseases than those that are fed without restriction. Monkey Study Photos of Monkeys in Study Negative Effects of Overeating

The content of the meal is very important both from a digestion and nutrition viewpoint. Three cups of cheese, salad, oil or bread, all have the same volume but will have drastically different effects. Factors that need to be considered are; density, calories and nutrient density.

- Density - In the digestive tract, the meal mixture should be a moist semi-solid mass that the stomach muscles can churn on and that the peristaltic waves of the intestines can easily propel forward. If it is liquid, there is nothing to grab on to, the feeling of fullness will not last and due to insufficient mass, being regular gets affected. If it is too solid or dry, like a meal that is mostly meat, cheese or refined bread, the intestines will have a difficult time to propel it forward. Meals that have a good portion of fruits, vegetables or whole grains (fiber) will make a good mixture.

- Calories - There is a dramatic difference in the calorie content of three cups of oil, ice cream or salad. Calorie rich foods should be used sparingly in the meal. For the bulky part of a meal, you can always eat as much fruit and non-starchy vegetables as you want without having to worry about calories. Foods that are high in fiber and water content should make up most the volume of the meal.

- Nutrient density - in order to be well nourished, eat foods that have a high ratio of nutrients (vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals) to calories. Again, these are the fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts. Diets that are high in refined carbs (sugar, soda, white flour) and/or fats can contribute plenty of calories, more than enough for a day, but still leave you short of your micronutrient needs. It can lead to being "overfed and undernourished".

Snacks:

Are snacks OK? Light snacks can be used between meals if you get hungry and weight is not an issue. In general, if you are not hungry, you should not eat but if you need something to hold you off until the next meal, a snack can help. Kids generally need a pick-up after school. Teens especially may need almost a mini-meal whereas adults may be satisfied with a lighter snack. Snack Ideas

Snacks are a great opportunity to score an additional serving of fruit in the day. Fruits digest very quickly and don't always mix well with cooked meals. They are great eaten alone or with a little yogurt or cottage cheese. A fruit smoothie or a handful of nuts (or pumpkin seeds) with some baby carrots are also great options. It's better to eat in one sitting rather than munching for a prolonged period and if eaten two or three hours before a meal, it should not affect your appetite for the next meal.

Food Combining:

Should food combining guidelines be followed? When I mention "food combining", I am referring the concepts developed by Dr. William Howard Hay in the 1920's often called the Hay Diet and later promoted by different health advocates (Herbert Shelton, T. C. Fry, Harvey Diamond, Robert O. Young, etc.). In Dr. Hay's diet, foods are classified according to their acid/alkaline response in the body; for instance as fruits (acid, sub-acid, sweet), starches (alkaline), proteins (acid) etc. There are general principles about what can be combined in a meal to promote good digestion. For example; protein and starch should not be combined in one meal since starch requires and alkaline environment and protein an acid environment to digest. With the advent of newer scientific information that has become available, these theories have been refuted. The digestive system has different stages that all food passes through regardless of type; the acid bath in the stomach, the enzyme step in the duodenum etc. So there is no problem with combining protein and starch in one meal. In fact, adding some protein to a meal will help moderate the rise in blood sugar levels from a carbohydrate. For a more detailed analysis reference Food Combining Myths and also Is Food Combining a Myth?.

Common Digestive System Problems:

A discussion of common digestive disorders is beyond the scope of this site. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) has good information on many common digestive disorders. Links are provided below for the most common ones.

Upper digestive system disorders:

GERD

Peptic Ulcer

Lower Digestive system Disorders:

Celiac

Constipation

Crohn's

Diarrhea

Diverticulosis

Flatulence

IBS

Lactose Intolerance

Many digestive system disorders develop over time and manifest in later years as the cumulative result of poor eating habits and/or food choices. Habits that that can cause problems include; eating at irregular times, skipping meals, eating irregular amounts, overeating, eating all the time, eating just before sleep, not staying hydrated, not answering the calls of nature, etc. Poor food choices include; lots of processed foods low in fiber and nutrients, refined carbs (white flour products, white sugar), high fat foods, meat, avoiding fruits and vegetables.

On the other hand, healthy eating habits and good food choices can help reduce the risk of many common digestive disorders. For healthy eating habits, see Tips for Good Digestion below. Good food choices include (you must be familiar with the mantra by now); abundant fruits, vegetables, whole grains and in moderation legumes, nuts & seeds and optionally low-fat dairy and eggs. Additionally;

- Exercise regularly and keep your weight in the normal range.

- Avoid foods that cause allergies.

- People who are lactose intolerant may be able to eat yogurt, hard cheeses or even milk in small quantities. Otherwise, try dairy with lactose removed, taking a lactase supplement with dairy or using soy substitutes instead.

Summary:

- The stomach produces gastric juices that kill germs and begin the breakdown of proteins. It can hold between 2-4 cups of food and usually empties within two hours after a meal.

- The small intestine is where most the digestion and absorption occurs. The pancreas secretes bicarbonate to neutralize the acidity and enzymes to further break down proteins, starches and fats. The gall bladder secretes bile to emulsify fats. The lower two thirds of the small intestine is where nutrient absorption occurs.

- The large intestine reabsorbs water and electrolytes. It stores the fecal matter until it is ready for elimination. Friendly bacteria aid in immunity and help to break down short-chain fatty acids and to synthesize biotin and vitamin K. Antibiotics can kill intestinal bacteria; probiotics such as found in yogurt and kefir, help to maintain intestinal bacteria.

- Typical transit time of a balanced meal in a healthy individual is about 2 hours in the stomach, 4-6 hours in the small intestine and 12-24 hours in the large intestine. Total time 18-32 hours. However for some it can be as much as 72 hours!

- Three meals a day is the most practical approach for most people. Two would be the minimum and more than three is generally not necessary unless there is a medical reason. Breakfast is considered the most important meal of the day, especially for children in school.

- Meals should be of sufficient volume to satisfy your hunger. The bulky part of the meal should primarily consist of high fiber, high water content (low calorie), nutrient dense foods; fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes. Do not overeat.

- Drink only small amounts as needed with meals to moisten dry food. Drinking large amounts can dilute digestive juices.

- A healthy snack can be used between meals if you get hungry. Do not eat if you are not hungry. Eat at one sitting and do not snack over prolonged periods. Have it 2-3 hours before a meal so as not to ruin your appetite.

- Food combining rules as developed in the 1920's are not supported by modern nutritionists. In particular, the idea that starch and protein should not be mixed in one meal is not valid. Most balanced meals will consist of a starch (carbohydrate) component to provide energy, a protein and a good serving of vegetables to provide vitamins, minerals and fiber. Adding some protein and a little fat to a meal can moderate the rise in blood sugar levels and help you to feel full longer.

Tips For Good Digestion:

- Sit or stand up straight while eating or drinking. Gravity helps move food down the esophagus to the stomach. When you slouch or hunch over, it puts extra pressure on the digestive organs.

- Chew well. Mixing food well with saliva starts the digestive process, makes it easy to swallow and when food is broken up into small parts it is more accessible to digestive juices. Large chunks only have their outer surface exposed to digestive juices and will only be partially digested.

- Reduce stress and eat in a relaxed manner. Tension can disturb digestion. Keep the atmosphere and conversation at meals light and friendly.

- Stay hydrated. Have drinks either 20 minutes before or 1 to 1½ hours after a meal. Only sip a light drink as needed during a meal to moisten dry food. Drinking lots of fluid with the meal can dilute the digestive juices.

- Do not drink ice cold drinks with a meal. They slow down digestion.

- Eat at regular times. The body adapts to routines. "Regular in" means "regular out".

- Do not overeat. Stop while you still feel comfortable. Overeating leads to discomfort and indigestion.

- Do not engage in vigorous activity after eating. It can suspend digestion and lead to cramps and feeling sick. However, moderate activity like walking is good for digestion.

- Do not lie down for one to two hours after eating. Laying down after a meal increase the chances of getting acid reflux.

- Eat at least two hours before sleeping. The system slows down while you are sleeping. Food can sit undigested for hours and disturb your sleep.

- Eating an occasional yogurt or kefir with live probiotic cultures can help to maintain a healthy bacteria culture in the large intestine.

- Include high fiber foods in your meals; fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes.

- To improve absorption of iron and other minerals, do not drink tea or coffee with meals.

- Avoid greasy deep fried foods.

Disclaimer:

The contents of this Web site are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Web site.

References:

- Thompson, Janice L., Melinda M. Manore and Linda A. Vaughn. "The Human Body: Are We Really What We Eat?" The Science of Nutrition San Francisco, CA : Pearson Benjamin Cummings 2008

- Duyff, Roberta L. "Planning to Eat Smart" American Dietetic Association Complete Food and Nutrition Guide Hoboken, NJ : Wiley 2006

- Craig, Winston J. "Beginning the Day With Breakfast" Nutrition and Wellness Berrien Springs, MI : Golden Harvest Books 2008

- Che, Chau Myths and Realities: Is Breakfast the Most Important Meal of the Day? Clinical Correlations June 18, 2009

- Anding, Roberta H. "Our Under Appreciated Digestive Tract", "Nutrition and Digestive Health" Nutrition Made Clear Chantilly, VA: The Great Courses 2009

| << Previous | Top | Next Topic >> |

Post a Comment